Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Final Summary

I set off by reading Peter Rowe and Seng Kuan’s book, Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China. This book gave me an overview of the development of Chinese modern architecture since mid 19th century, and how the problem of “keeping Chinese identity and embracing modernism at the same time” has plagued to Chinese architects ever since the introduce of modernism in China. Then, I looked into the major architectural styles of Chinese vernacular architecture, and sorted them into four categories according to their major features. Next, I mainly focused on the vernacular architecture forms of southeast China and studied their origin, features and mechanisms. Four major examples I studied are Huizhou vernacular architectures, the water system planning of the buffalo shaped village in Huizhou, Jiangnan water towns and waterfront preservation today, Fujian earthen houses (Tulou). Interestingly, each of these different topic gave me a different perspective to look into architecture and design. As a result, I have touched different aspects of shaping the built environment, including architecture, urban planning, landscape design, water system planning and communal housing issues. I want to especially thank my advisor Professor Michael Davis, whom gave this independent study an extraordinary width by providing me many cross-cultural perspectives. Under his help, I viewed each issue in a broad way by comparing each vernacular form with similar projects around the world. This blog served as a journal to record my research process, where I’ve posted the pictures I took or collected, articles I like, drawings and analysis diagram I did, as well as the writings from my each sub research topic.

Through this independent study, I got a deeper understanding of the social, historical and functional context of different vernacular architecture design. I was also constantly amazed by the cleverness of people in the ancient time, how they could utilize the force of nature to achieve something that we need to achieve by machines today. I was taught an important lesson that a good architecture design is always based on a throughout understanding of the site and the nature.

At the same time, my study also gave rise to another question: when we can achieve the same thing by nature and by machine, should use machine or let nature to do it? I think there is no absolute answer to this question. Personally I believe that we should not object the use of machines if they can make the process quicker and more efficient, but if the efficiency is based on the sacrifice of nature resource and environmental pollution, we should really call the use of machine into question. Furthermore, there lies an even more complex question of how to calculate the cost and benefit of the “machine approach” and the “nature approach”. I guess that is also why those green building rate systems such as LEED are often put into big controversy today.

Furthermore, I feel the Modern Architecture class I took this semester also helped me a lot in finding an answer to the “big roof controversy”. By studying at the ideas, theories and projects of architects since late 19th century, I was excited to find that many architects, such as Antoni Gaudi, Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Khan, stand in the same line with me as turning to historical and vernacular architecture as their design inspiration. Meanwhile, I actually feel that the more I know, the less certain I am on my original view point that “big roof approach is superficial”. Le Corbusier, De Stiji and Bauhaus architects’ ardor in searching for a universal style should not be condemned simply because they were detached from history and localism; they are just some idealistic minds who want to bring human being a simpler, more equal and efficient. In the end, I found all my puzzles and wonders were best answered by Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture: architecture should look into history but borrowed them in a way that is suitable to the contemporary context. A big roof without particular function built in can still be considered useful as long as it can reminds people the historical meaning it wants to convey (the “vestigial elements” mentioned in Venturi’s book). Maybe in architecture, there is just no absolute cut line between right and wrong, and that’s exactly reason why architecture has been such an intriguing subject that constantly arouses people’s interest to seek for the “best possible answer”.

My final part of this independent study includes three recent projects in China which I personally believe that they combined traditionalism and modernism in a well-balanced way. They translated and abstracted the traditional elements into a beautiful modern language. I feel like I can’t wait to know more about architecture, both theoretically and practically, so that I could start my journey of searching my “best possible answer” to contemporary Chinese architecture.

p.s. It was a pity that I only got to looked into 4 out of 12 major forms of Chinese vernacular architecture in depth due to the time limit, but I was glad that I made a good start. After this semester’s independent study, I am more and more certain that there is actually a lot of research value in Chinese vernacular architecture. I think there is still much to improve in my current research and I am also thinking about turning this topic into my senior thesis topic.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

Case Study: Frangrance Hill Hotel

One major feature of the hotel is the use of succinct geometric forms. Square, triangle and rhomboid are Pei’s signature design elements. We have seen the use of it in his many other project for modern office building, such as the Bank of China building in Hongkong, and the Louvre Glass Pyramid in Paris. In the Fragrant Hill Hotel, this minimal modernist element was used again, but was rendered in a way that was naturally transformed into an abstraction of Chinese vernacular architecture form. Pei largely used the geometry forms in the windows, which was echoing the traditional shaped-window in Suzhou gardens.

One major feature of the hotel is the use of succinct geometric forms. Square, triangle and rhomboid are Pei’s signature design elements. We have seen the use of it in his many other project for modern office building, such as the Bank of China building in Hongkong, and the Louvre Glass Pyramid in Paris. In the Fragrant Hill Hotel, this minimal modernist element was used again, but was rendered in a way that was naturally transformed into an abstraction of Chinese vernacular architecture form. Pei largely used the geometry forms in the windows, which was echoing the traditional shaped-window in Suzhou gardens.

(the repetition and variaion of simple geometric forms)

(the repetition and variaion of simple geometric forms) (the geometric windows in traditional Suzhou gardens)

(the geometric windows in traditional Suzhou gardens)The plan of the hotel also shows the wisdom of traditional Chinese garden design principle. When you look at the front entrance, the high rising walls hide everything inside and give one a mysterious feeling. However, as you enter into the central atrium, the space suddenly burst out as a well-lit environment. The tall trees and waters built in the atrium make one even hard to tell if it is inside or outside. The backyard garden of the hotel is an even opener space, with lakes, zigzag bridges, man-made rocks and high risen trees.

(comparison: high-rise parimeter walls at the entrance concealed the bigger world inside. left: entrance of Frangrant Hill Hotel; right: a traditional high-rise wall entrance in Huizhou)

(the central atrium of the hotel)

(the central atrium of the hotel)

(the back garden of the hotel)

(the back garden of the hotel)Underlying the design is a strategy to provide a "Third Way" wherein advanced Western technology is grafted onto the essence of Chinese vernacular architecture without literal imitation. The skylight was the only major imported component; everything else was constructed by local craftsmen using age-old techniques and materials. Fragrant Hill thus draws from the living roots of tradition to sow the seed of a new, distinctly Chinese form of modern architecture that can be adapted, not merely adopted, for diverse building types.

(the well-lit central atrium; the shades of the skylight roof was made of local material, bamboo)

(the well-lit central atrium; the shades of the skylight roof was made of local material, bamboo)Each guest room opens onto a courtyard through a shaped "window picture" that frames the landscape and brings the outdoors inside. Building and gardens merge inseparably in an intimate reciprocal relationship. This “framing landscape” technique is actually a common gardening technique used by the designer of Suzhou gardens.

("framing landscape" in Frangrant Hill Hotel)

("framing landscape" in Frangrant Hill Hotel) ("framing landscape" technique used in a traditional Suzhou garden, Zhuozheng Yuan)

("framing landscape" technique used in a traditional Suzhou garden, Zhuozheng Yuan)

the same beautifully cast shadow from the shaped-window in Frangrant Hill Hotel(left) and Zhuozheng Yuan, Suzhou(right)

Architect: I.M. Pei, C.C. Pei

Location: Beijing, China

Completion: 1982

Mechenical/Electrical: J. Roger Preston, Hong Kong

Interior: Dale Keller & Associates, Hong Kong

Awards: 1984 American Institute of Architects: National Honor Award

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

Case study: China Academy of Art

China Academy of Art (CAA) is one of the most influential art institutions in China. Located in Hangzhou, its new campus was completed in 2006. Designed by the dean of the architecture school of CAA, Shu Wang, the new campus took a very crude and natural appearance and borrowed a lot of elements from vernacular architectures from Southeast China.

(College of Visual Art Building, China Academy of Art)

(College of Visual Art Building, China Academy of Art)The College of Visual Art building was designed in a four-sided courtyard shape, with a big courtyard at the center with is similar to tianjing (skywell) in Huizhou and Zhejiang vernacular architecture. The verdant corridors facing toward the tianjing were closed by wooden windows, which are open most of time and can be closed during windy typhoon season.

The buildings of the architecture department are basically boat-like building built on water. They were like the stone boat in Chinese royal gardens (see the stone boat from the Summer Palace, Beijing).

(left: Stone Boat, Summer Palace, Beijing right: Architecture Building, Chinese Academy of Art)

The façade of the Scultpture Department building were built in recycled materials, such as broken tiles, bricks, porcelain. It is said that one of the designers of this building, who is a faculty at CAA, took his students on sketching field trip and asked them to collect these deserted materials during the field trip. It is definitely a very avant-garde building in China both in terms of its appearance and environmentalist concept.

(The facade of the Sculpture Department Building is made of recycled tiles)

(The facade of the Sculpture Department Building is made of recycled tiles) (Administration Building, China Academic of Art)

(Administration Building, China Academic of Art)

Monday, December 7, 2009

When Chinese Tulou Meets the Unité d’Habitation

I. A brief overview of Tulou Houses

War and conflict often bring about the destruction of architecture. However, to the Hakka people in southern China, these forces result in new constructions that define a cultural identity and place. In the southeastern Fujian Province of China, Hakka people built many fortresses like communal living buildings known as Tulou. Tulou can be in either square or round shapes, and they usually share the following features:

Concentric Geometric Forms: A Toulou is composed of several concentric circles or squares, with the outmost one tallest and the inner ones have decreasing number of stories.

Natural Material: The walls of Tulous are built with rammed earth and the structure of the building is built with wood. The maximum strength of the rammed earth is achieved by mixing the earth with sand, sticky rice and brown sugar. The whole structure is not built with a single metal nail; conjunctions are all achieved by wooden or bamboo nails.

Defense Purpose: In order to keep the residents of Tulou away from bandits and outside intruders, Tulou typically has only one entrance way, and the thick wooden entrance door is covered with iron. There are no windows at ground level and only very few windows are placed at the upper levels of the exterior wall. There are many small gun ports at upper level of the exterior wall which were used for shooting guns from inside. A building could withstand a protracted siege by being well-equipped with food and an internal source of water; Tulou also has its own sophisticated sewage system. The exterior earthen wall is extremely thick, usually up to six feet.

Family Communal Living Pattern: Each tulou houses a big family clan, with up to 80-100 families and as many as 500-600 inhabitants spanning three or four generations. The largest Tulou found today covered over 430,000 sq feet. Each sub-family owns a vertical unit. Each tulou is an amazing self-sustaining micro-community sufficient with food storage, space for livestock, living quarters, school, temple, armories and more. Typically, the outmost circular building is for private living space while the central buildings are public space. When the population of the clan grew, the housing expanded radially by adding another outer concentric ring, or by building another tulou close by in a cluster.

Building Plan Reflects Family Order and Social Belief: The interior layout of Tulou rigorously follows the family order and ethical codes Hakka people believe. Hakka people pay high respect to the elders; they build ancestral hall to commemorate their ancestors. The ancestral hall is placed at the innermost loop of the concentric circles and is also on the central axis of the building. In history, Hakka people were forced to move several times from the central plain area of China due to warfare, scarcity of resources and famine. The severe living conditions and constant moving experiences made Hakka people extremely united. This sense of unity and equality is reflected in tulou in that the high condensed private bedrooms are all uniform. People get same housing regardless gender, age and family status. Hakka people values study and knowledge a lot, so there is school built in each tulou community, and the school is put at the inner circles. All branches of a family clan shared a single roof, symbolizing unity and protection under a clan; all the family houses face the central ancestral hall, symbolizing worship of ancestry and solidarity of the clan.

The exact period in which tulou first appeared is not known. It is believed that they originate from the 13th or 14th century or even earlier, but most tulou we can see today were built in 19th century and early 20th century. Because of their mountainous and sometimes secluded locations, Tulou is not widely known to the architecture world until 1980s, and it was once seem as UFO from outer space and China’s secret nuclear base. In 2008, UNESCO granted the Tulou “apartments” World Heritage Status. The change in historical and social context made the Hakka people no longer need to build a building with such defensive purpose, but tulou is still of great research valuable. First, the building material is totally organic, it is taken from nature and is degradable by nature. The rammed earth material is also good at adjust the temperature and humidity of the interior environment, serving as a natural cooling system. Second, Tulou proposed possible way of the communal living pattern, which may be very helpful to our increasing need of high-density communal living structure.

II. Comparison: Solution to the Communal Living Problem--Unité d’Habitation vs. Tulou

Both the Unite d’Habitation in Marseille by architect Le Corbusier and the Tulou dwellings by Hakka people in China provide a unique way to solve the question of communal living structure. Although the two structures are extremely far away from each other in terms of time and geographical location, the shared some common approaches yet possess their own philosophy. I’m going to compare these two structures from the following aspects:

Social and Natural Reasons for A Communal Living Structure

The Unité d’Habitation and the Tulou arise from a similar social need for a high density communal dwelling with less space. Le Corbusier once argued his favor of a vertical city as follow:

Man has become a slave to his environment, which owes its origins to circumstances rather than to human design. The ideal city would cover less ground, accommodate more people and yet, 85 percent of its area would be open space. How? By building it upwards as a vertical garden city.

Despite Le Corbusier’s desire to experiment his great vision for a vertical city, the Unité d’Habitation was built because of a historically acute housing shortage in Marseille. In 1945, World War II made 50,000 people in Marseilles homeless, so there was an urgent need for a communal housing structure. Similarly, the origin of Tulou was a reaction to the much restricted local landscape and an increasing number of peoples need to be housed.

The landscape and site conditions in these two projects are also very similar. Both places share the same strip-like landscaped (see figure 1). Southwestern Fujian is enclosed by mountains, while Marseilles is a city sprawls outwards from a harbor and shaped by ocean and mountains. The limited land also requires the building to take an upward form.

The Living Cellular

One major big difference in these two approaches to communal living structures is the plan of individual living spaces, namely, the “cellular” in the buildings. In the Unité d’Habitation, Le Corbusier designed 26 variations of apartment forms, and all of them are based on the same concept of “interlocking flats”: a long, narrow two-storey apartments run the entire width of the Unité at one level, and half its width on the next, and in this way apartments in two successive floors are interlocked together, living a open central space in the middle served as “la rue intérieur”, or interior road. In this way, the living rooms are extended up through two stories. At each end of the room, the external walls are completely glazed behind brise soleil, which can be folded back to form a shallow balconies. The reveals of the balconies are painted in different colors. This polychrome character creates an illusion of spaciousness. For the viewer who standing in front of the huge building blocks and looking at the building, a polychronmy façade breaks up the over-large surface and create an effect of kaleidoscope.

In contrast, the tulou building’s individual living space is not that spacious compared to the Unité. Each person only get a one-story private bedroom, and the common family space such as living room, kitchen and dinning room is shared by the people who lives in the same vertical unit. The staircase in tulou takes up the space of a vertical unit, instead of interpenetrating in the apartments. People moves within the same floor through a circular verandah facing the central courtyard of the building. The space of private living cellular in tulou is less than the Unité partly because the inhabitants in tulou are all members of the same big family, so they may feel more comfortable with sharing a single big living room with the people in the same vertical unit.

Public Spaces and Communal living Facilities

Part of Le Corbusier’s vision of the vertical city is that, “with our modern techniques, mankind must be rehabilitated in conditions of nature. Sun, space and trees are essential joys.” He achieved this point by building a lot of public green space around the Unité for people to enjoy the nature. Another spotlight of the Unité is its roof garden, where a swimming pool and many other public facilities are placed. Given tulou’s defensive purpose, it is hard to exploit nearby space to build public garden like the Unité. The inside of tulou seems lack of green space either, since the floor of the public open space are all paved pebble roads. But the amount of sunlight, fresh air and rainwater is still ensured by the central open space, or tianjing (skywell).

One of the most controversial design in the Unité is its placement of the shop and restaurants in the middle floor. Many people argue that by enclose the shops in the middle of the building instead of open them at the ground floor, the shops become exclusive to the only residents of Unité, and these shops are also unlikely to pay their way. It sealed off outside customers and failed to facilitate the social integration between the Unité and the neighborhood communities. In contrast, although the placement of public gathering space at the center of the tulou is determined by traditional belief and social value, it nevertheless seems to be a good design solution. A central placement avoid unnecessary interruption of the upper private living floors and may create a community centripetal force by utilize the central space.

III. A Corbusian Tulou

After looking at the good design concepts in the Unité, I come up with a Corbusian plan for tulou, aiming at improve the living quality of the residents in tulou with modern design approach. Details please see the section diagram for the Corbusian Tulou.

(click image to enlarge)

(click image to enlarge)IV. Some Final Thoughts: The Practicality of Unité and Tulou-like communal dwellings in the future

It is true that with an increasing population growth and less and less available lands, we will need more communal living structures in the future. However, do we really need a self-contained form of communal dwelling like the Unité and Tulou? A self-contained dwelling may be convenient for the life of peoples inside, but it at the same makes the building become an insular island. A self-contained dwelling structure is not good for maximizing the use of public facilities, may cause a huge waste in resource, and will also be bad for fostering a sense of neighborhood with other nearby dwellings. Some left wing critics even argue that the Unité is going to be un palais pour snobs if it continue to develop in this exclusive way.

However, if this kind of self-contained communal dwelling is located in suburban areas where public living facilities are relatively scare, the well-equipped Unité does have some incomparable advantages. This makes me think about further develop the form of Unité into a prototype for a future home built in severe natural environment. We may enclose the whole building with a huge glass cover so that the interior temperature can be totally under control; we may also make it into a prefab house that is easy to assemble. In that way, we may build these houses to area such as desert and rainforest where is currently considered as places not suitable for human living. This also makes it possible to conduct long-term and big team scientific expenditure to the Antarctic and outer space.

Another thing that is worth pondering is that the well functioning of the Unité and tulou actually requires a strong community responsibility supported by all tenants living in. Unless the tenants are cooperative, the whole fabric of collective living is likely to collapse. In this sense, the plan for a Unité is somewhat like a proposal for a dwelling in a communism society, a utopian world. This problem of community responsibility is easier to solve in the case of tulou given its tenants are all from the same big family. In a Unité where tenants are all unfamiliar with each other, it takes everybody’s moral improvement to maintain the order of the Unité. Although it may be a little bit hard to realize at the moment, but it may not be a bad way to teach people how to live in high moral standard world. This point perfectly illustrated Le Corbusier’s idea that if you life in a chaos building structure, you will lead a chaos life; if you live in a building structure of good order, your morality will be improved by the building.

Monday, November 23, 2009

Jiangnan Water Towns and Its Potential Development in the Modern Time

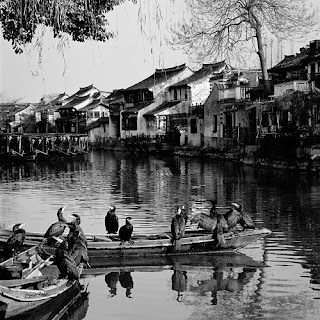

Crisscrossed with countless canals, the Jiangnan or Yangtze Delta region in southeast China is dotted with water towns which are among China’s richest cities. Its remarkable hydrography makes the area’s traditional life pattern closely tight to the omnipresent water environment. During a time when waterway was the major transportation, the canals in Jiangnan provides the water towns more access to business. The built of the Grand Canal in Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD), which connects the capital Beijing to the Jiangnan water town Hangzhou, further pushed the economic trade and cultural exchange of the north and south China. Ever since the Sui Dynasty, the word “Jiangnan” has been closely associated with the word “prosperous”. Dwellings in Jiangnan water towns are usually two stories high, and are built right by the canals. The first floor is usually for residence shops, while the upper floor is for private residences. The architectural style of the buildings in Jiangnan water towns is very similar to that of the Huizhou area, with black tile roofs, white plaster walls and central skywells. However Jiangnan residences don’t have the high perimeter walls that envelope the whole building. Instead, they open the buildings right to the waterborne environment around.The scale of the buildings in Jiangnan is also smaller compared with that of Huizhou, since the landscape in Jiangnan is largely confined by the canals. Various elegant waterfront structures, such as stone docks, waterside pavilions, teahouses and stone bridges are the hubs of the daily activities of the Jiangnan water towns.

Crisscrossed with countless canals, the Jiangnan or Yangtze Delta region in southeast China is dotted with water towns which are among China’s richest cities. Its remarkable hydrography makes the area’s traditional life pattern closely tight to the omnipresent water environment. During a time when waterway was the major transportation, the canals in Jiangnan provides the water towns more access to business. The built of the Grand Canal in Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD), which connects the capital Beijing to the Jiangnan water town Hangzhou, further pushed the economic trade and cultural exchange of the north and south China. Ever since the Sui Dynasty, the word “Jiangnan” has been closely associated with the word “prosperous”. Dwellings in Jiangnan water towns are usually two stories high, and are built right by the canals. The first floor is usually for residence shops, while the upper floor is for private residences. The architectural style of the buildings in Jiangnan water towns is very similar to that of the Huizhou area, with black tile roofs, white plaster walls and central skywells. However Jiangnan residences don’t have the high perimeter walls that envelope the whole building. Instead, they open the buildings right to the waterborne environment around.The scale of the buildings in Jiangnan is also smaller compared with that of Huizhou, since the landscape in Jiangnan is largely confined by the canals. Various elegant waterfront structures, such as stone docks, waterside pavilions, teahouses and stone bridges are the hubs of the daily activities of the Jiangnan water towns.

Jiangnan watertowns, in some ways, are very similar to the world’s famous water town Venice, Italy. Stretches across 118 small islands in the Venetian Lagoon, Venice’s daily life if largely depend on water-traffics. The city has 117 canals and 401 bridges, with the major canal, Grand Canal running through the center of the city as the major traffic corridor. Jiangnan water towns are similar to Venice in that they are also run through by a central canal, the Grand Canal of China, and crisscrossed by hundreds of small canal branches. Similar to Venice, Jiangnan water towns’ major traffic is also water way. What’s more interesting, Jiangnan water towns even have a counterpart of the Gondola, which is called black-awning boat. The architecture of Venice and Jiangnan water towns is slightly different. Although both used the form of stilt houses, Venice’s houses are often in direct contact with water. Also strikingly similar are the economies of Jiangnan water towns and Venice. They were both the leading commerce centers of their local area in about a thousand years ago. Given the similarity in their waterborne environment and prosperous economy, Jiangnan water towns were often called as “Venice in the East”.

Venice and Gondola vs. Jiangnan water towns and black-awning boat

However, with the rapid development of highways, automobiles, railways and other landway traffics, the role of water traffic played in trade and commerce is weakening. In recent decades, in a rush to modernize and industrialize, far too many traditional water towns hastily sacrificed their past forms in the process of building new houses and factories, filling in canals and the constructing roads. As a result, the formerly vibrant Jiangnan canal network is in very bad conservation, may tributaries of the Grand Canal faced the problems of clogging, water pollution, and may parts of the Grand Canal is even no longer navigable. How to conserve, redevelop and rediscover the potential use of waterfronts became a great challenge to Jiangnan water towns.

Here we are going to look closer at Hangzhou, one of the prosperous Jiangnan water towns and its strategy of water channel conservation. The city of Hangzhou is the terminal of the Grand Canal. The canal runs through the northern part of the city. Starting from 1996, the government of Hangzhou carried out a Grand Canal Redevelopment Project, and its first phase was completed in 2006 with rather remarkable effects. The master plan centered on the spatial and functional redevelopment of the waterfronts, with is main goal as making the Grand Canal better serve for people’s modern life. In the project master plan, the new waterfront of the Great Canal is going to have multiple functions; it will not only keep its traditional water traffic function, but also incorporate functions such as ecological center for species, public parks and convene space, historical and cultural center, and tourism spot. These goals were achieved by the government’s effort in cleaning the watercourse to facilitate the barges, building public parks, opening public water transportation such as waterbus, and establishing a Grand Canal Museum which records the history and cultural relics of the canal.

Building and redeveloping a great waterfront to serve for a better urban public space is not just a problem faced by old water towns like Hangzhou, but is also the shared questions of many waterside cities in the world. Having looked into several successful cases of waterfront redevelopment in the world, I summarized several major points of how to build a successful waterfront.

1) The planning of the redevelopment of water front should start with looking at the big picture of the city—what role is the waterfront going to play in the city? Do we want it to be the central artery of the city where the city unfolds and radiates from, or we want it to be only a center of a part of the city? The answer to this question largely depends on the natural location of the waterway. For example, the Seine River runs through the center of Paris, so the central location of the river enables the waterfront to become the focal point of the city. In contrast, the Brooklyn Bridge Park, which lies in the east side of Brooklyn, would be better planned as a local community gathering space. The Grand Canal runs through the north part of Hangzhou city, where used to be the industrial region of the city, and ends at the downtown district of Hangzhou. This location may let us plan the waterfront as have dual roles: in the northern industrial district it may serve as the public green space for local communities, while in the downtown part it may serve as the cultural and commercial center of the city.

2) Public goals should be set as the primary goal. Avoiding the waterfront from becoming seclude to a small community is the key of keeping the dynamic and liveliness of the waterfront. A negative lesson can be draw from the planning of the Brooklyn Bridge Park. Several high residential towers inside the park and at the entrance of the park made the Brooklyn Bridge Park unfriendly to the larger community, because people tend to think the park is only open to the upscale residents of adjacent Brooklyn Heights. Therefore, a great waterfront should not be dominated by residential development, because a high concentration of residential development undermines the diversity of waterfront use by creating pressure to prevent nighttime activity from flourishing.

3) Integrate the waterfront to the city’s overall transportation system. Although the status of water traffic is supplanted by railways, automobiles and metros, it is still a good alternative of the often over-crowded landway. Therefore, Hangzhou’s step in opening up waterbus lines is a really good idea to revitalize the water traffic. Meanwhile, it is also helpful to build other public transportation lines and stops cross the waterway or at the waterfront. For example, the Paris metro system goes along and across the Seine, which brings people to the waterfront from all over the city.

4) Avoid building a uniform waterfront; different parts of the waterfront should have its own characteristics. The characteristic of different waterfront parts should relate to its existing assets and the context of neighborhood. This means that the waterfront in a certain region should strive to showcase the local identity. How to revitalize the waterfront relationship with the northern industrial district of Hangzhou can draw a lesson from the design and planning of Granville Island, Vancouver, Canada. Originally shaped for industrial use in 1913, the buildings on Granville Island deteriorated until a planning process for the island's redevelopment in the 1970s, where many vestiges of the industrial past were still retained, but transformed into an inviting public activity space by welcoming the move in of art community. Actually the idea of transforming former industrial buildings into art community is no longer novel, and Hangzhou is already taking this step. The former factory building of Hangzhou Silk Company now becomes the studio space for artists and musicians. All that we need to do is to further increase the popularity of the place to create a bigger influence in the city of Hangzhou.

5) Creating destinations or point of attractions. The linear shape of canals and rivers is very likely to make the waterfront become a prosaic pathway to a destination somewhere else. In order to avoid this, the waterfront itself should become a destination, a centerpiece for programming and activities. PPS (Project for Public Spaces), a New York based nonprofit organization dedicated to creating successful public places for communities calls the process of creating ten (or several) great destinations along a waterfront the "Power of Ten." This focus on destinations, rather than "open space" or parks, enables genuine community-led stakeholders such as business, residences and institutions to take root.

6) Balance Environmental Benefits with Human Needs. While a wide variety of social uses can flourish on a waterfront, successful destinations usually embrace their natural surroundings by creating a close connection between human and natural needs. This requires a tight work with marine biologists and environmentalists in planning of what to plant along shorelines, devising a method to improve water quality and revive fish and wildlife habitat. Boardwalks, waterside playgrounds and picnic areas can be incorporated into the shoreline design without sacrificing environmental and social benefits.

7) Last but not least, a good preservation by both the government and the public.

To sum up, we can see that the problem of how to build a better waterfront is confined by the existing landscape and urban layout, but a successful planning of waterfront can also shape the existing environment. Although the traditional waterborne life pattern is no longer applicable to the change in technology and modern lifestyle, there’s still potential to maximize the use of traditional waterways, and I believe this everlasting changing and adaptation just shows what we mean by sustainability.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Riverfront Planning: Planning of the Grand Seine, Paris

http://www.world-heritage-tour.org/europe/france/paris/map.html

(go into the website and click on the specific images on the map to see lager 360 panaroma)

Friday, November 20, 2009

Great Waterfronts of the World

The following is an article I found during my research on waterfront planning, which listed several most successful waterfronts in the world.

A truly great urban waterfront is hard to come by. The PPS staff has examined more than 200 urban waterfronts around the world--cities on the sea (Hong Kong, Vancouver, Miami, Athens), rivertowns (London, Paris, Buenos Aires, Detroit), and sturdy lakefront burgs (Milwaukee, Chicago, Cleveland, Zurich). It is exceedingly rare to find a waterfront that succeeds as a whole, although there are promising elements in almost all of them. So when we sat down to share our notes about which waterfronts deserve to be called the world's best, it only made sense to create two categories. The first, "Waterfront Cities," considers the entire waterfront--how well it connects by foot to the rest of the city and sustains a variety of public activities in multiple areas. The second category, "Waterfront Places," looks separately at individual destinations along the water. When you experience these extraordinary public spaces, you realize how much more would be possible with a coordinated strategy to make the whole waterfront a place for people.

Best Waterfront Cities

These six cities offer a taste of what's possible. They vigorously incorporate the waterfront into the broader life of the community, using it to showcase their best assets. By exploring the water’s edge you can get a sense of the whole city

1. Stockholm, Sweden

2. Venice, Italy

3. Helsinki, Finland

4. San Sebastian, Spain

5. Sydney, Australia

6. Hamburg, Germany

Best Waterfront Places

The following spots are the best of the best of waterfront public spaces. To visit any of them leads to the inevitable question: Why aren't there more places like this? Every city needs places on its waterfront with the qualities and sheer appeal of these destinations.

1. Market Square and Esplanade, Helsinki, Finland

As PPS likes say about all great squares, this spot reaches out like an octopus, drawing people toward it—both from the city streets and from the waterborne routes of the bay. The most remarkable "tentacle" is the esplanade that leads here from the heart of the city. Walking down to the shore on this path is a finely paced, tantalizing journey--a veritable study in how to take advantage of a waterfront setting by building anticipation and heightening the senses on the route there.

2. Paris Plage, Paris, France

3. Nyhavn and Kongens Nytorv Square, Copenhagen, Denmark

4. Granville Island, Vancouver, British Columbia

5. Venice Beach, Los Angeles, California

6. Riverwalk, San Antonio, Texas

Yes, Riverwalk is a tourist magnet, but don't let that fool you. San Antonians come here in droves too. Most impressive is that people choose to come to Riverwalk all year round, even in the oppressive heat and mugginess of a Texas summer. For one thing, the water and shade cool things down--an important quality of waterfronts everywhere that we often overlook. And besides, why worry about the heat when you are surrounded by such a beautiful setting and such fascinating crowds?7. People's Park at Islands Brygge, Copenhagen, Denmark

8. Main Beach Park, Laguna Beach, California

9. Ribeira District, Porto, Portugal

10. Aker Brygge Harborfront, Oslo, Norway

11. City Hall, Stockholm, Sweden

12. Coney Island and Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, New York